The week of April 16th, there will be just one destination for followers of spaceflight and aviation in general: Washington, D.C. Why? The arrival and public display debut of the first of the retired American space shuttle orbiters, Discovery. Discovery will take to the skies for the final time on April 17, winging her way north from Kennedy Space Center aboard one of the two modified Boeing 747s that previously carried her home to Florida from landings at the dry lake bed at Edwards Air Force base in California.

Although there will be no public access to Discovery’s arrival at Dulles International Airport in the mid-morning hours of the 17th, it’s likely that spotting the two aircraft in flight was not be that hard. And for those not able to reach the nation’s capital, details of Web broadcasts covering the landing should be announced in the near future.

Over the next two days following the orbiter’s arrival, the huge spacecraft will be de-mated from the 747 and prepared for towing to her new home, the National Air and Space Museum’s Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center, located near Dulles. On April 19, a public celebration will commemorate the transfer of responsibility for Discovery’s caretaking from NASA to the museum, where visitors will see not only the new arrival but also the early flight prototype orbiter Enterprise, which just days later will head north on her own journey to a new home at the Intrepid Sea, Air & Space Museum in New York.

Details on the National Air and Space Museum “Welcome Discovery” events can be found here: http://www.airandspace.si.edu/collections/discovery/

Discovery will always have special meaning for me. She the first space shuttle I saw head “uphill” into orbit, carrying the Hubble Space Telescope into space on April 24, 1990. But more recently, in June 2011, I was invited to visit and board Discovery as preparations got underway for her new, post-retirement life.

Here’s a look at Discovery within one of the Orbiter Processing Facility buildings at Kennedy Space Center.

Above, the entrance to the Orbiter Processing Facility where much of the museum preparation work took place. For years, the OPF buildings had a far different charge: to prepare the orbiters for flight into space.

The OPF environs are cramped, with no location offering a panoramic view of the entire orbiter. Dead ahead, one of Discovery‘s landing gear.

Discovery‘s nose, with the on-orbit maneuvering systems taken out to remove harmful propellants.

The intricate patchwork of protective tiles guarding the orbiter’s underside.

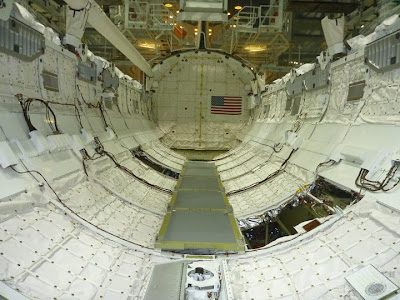

A look into the payload bay. Using the remarkable Canadarm robotic arm seen in the foreground, the Hubble Space Telescope – and many other payloads over the years – were deployed into orbit.

A view into the mounting areas of the three Space Shuttle Main Engines, the liquid-fueled engines that worked with the Solid Rocket Boosters to shove Discovery “uphill” into space.

On board Discovery, this air lock provides access to the payload bay from the orbiter’s mid-deck.

Passing through the mid-deck airlock yields this amazing view of the payload bay.

Discovery‘s upper flight deck, with the commander’s consoles on the left and the mission pilot’s on the right. There is an area of just a few feet from the back of the seats to the rear bulkhead of the flight deck. Spacious it is not.

Of all the places that I ever thought I would visit, this is one location I never saw myself. To be on board what is quite likely the most complex vehicle ever built by mankind was a tremendous experience. It will be well worth your time to take a trip to the National Air and Space Museum to see Discovery up close for yourself.