This week, the second man to set foot on the moon will be a keynote speaker at a conference designed to exchange ideas about a much more complex mission: sending men to Mars. Buzz Aldrin will be Wednesday’s keynote speaker at the Humans 2 Mars Summit being held at George Washington University, discussing the call for further human exploration of space detailed in his new book Mission to Mars. Others speaking at the three-day even that kicks off today include NASA chief Charlie Bolden and Dennis Tito, the man behind a recently-announced private mission to Mars covered in an earlier posting of Aerospace Perceptions.

Buzz Aldrin has always been something of a controversial figure, during his military career and in the wake of his flight to the lunar surface on Apollo 11. In fact, while on the moon, Aldrin – a Presbyterian church elder – secretly carried out a communion service with a small kit, an action forbidden after atheist activist Madalyn Murray O‘Hair brought a lawsuit over a Scripture reading during Apollo 8‘s Christmas, 1968 lunar orbit. In darker days that followed, Aldrin suffered from depression and alcoholism, a period Aldrin himself has addressed in his books. I’ve heard him described as cold or standoffish by people who have encountered him, be it at book signings or other events. I can’t say I met him at a book signing several years ago, as he didn’t even look up from signing my copy.

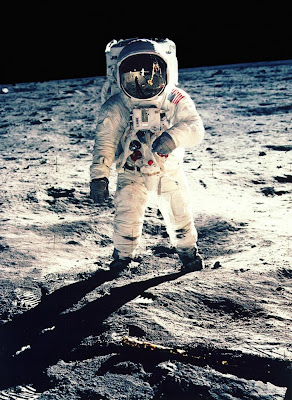

|

| Perhaps the most famous NASA photograph: Buzz Aldrin, as photographed by Neil Armstrong. |

Aldrin also tends to be a magnet for criticism for commercializing his role as moonwalker. Buzz has appeared on Dancing with the Stars and voiced

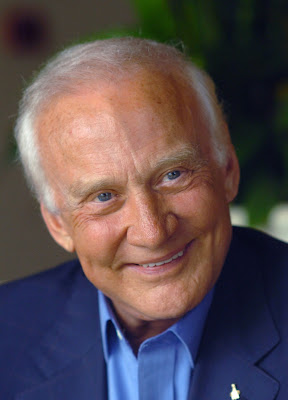

|

| Buzz Aldrin in recent years. |

To all that I say: so what? Despite the rare fraternity that Buzz became the second member of on that July day in 1969, he is still a human being, subject to the same long litany of bad decisions and problems that litter all of our lives. I’ve been fortunate to meet several of the Apollo astronauts over the years. Pete Conrad, who walked the lunar surface on Apollo 12, came across as serious. Harrison Schmitt, lunar module pilot of the last flight to the moon on Apollo 17, was gregarious. But they’re all different people. And nothing Aldrin could ever do to stir public disapproval can change the significance of the risks he took for the advancement of spaceflight more than forty years ago.

In the sports-mad Philadelphia area, where I live, even players who famously blew a play can live like local royalty, all faults forgiven. It seems strange to me that a man who successfully undertook one of the most dangerous, frightening, and glorious human endeavors can be the target of so much criticism for being just that: human.